Nothing Brings Success Like More Success

Why AI, markets, and the economy are becoming increasingly winner-takes-all — and what we can do about it.

Hey friends—Mercury’s Playbook is back. How is 2026 treating you?

I’m a week away from starting one of my final semesters. I begin with a course on the Business Drivers of Industry, along with a separate and very exciting project on Generational Balance. In the second half of the term, I’ll be Teacher’s Fellow for a Tech Product Management course that I accidentally aced. This is in addition to my job, personal life, and other writing endeavors. Busy? Yes. But I should have a lot of great insights to share.

Today’s dispatch is an illumination of a massive shift that has been taking place in economic markets for at least three decades, yet hardly anyone seems to be talking about it. If you aren’t subscribed, make sure you do so by using the button below—and don’t forget to share with your friends.

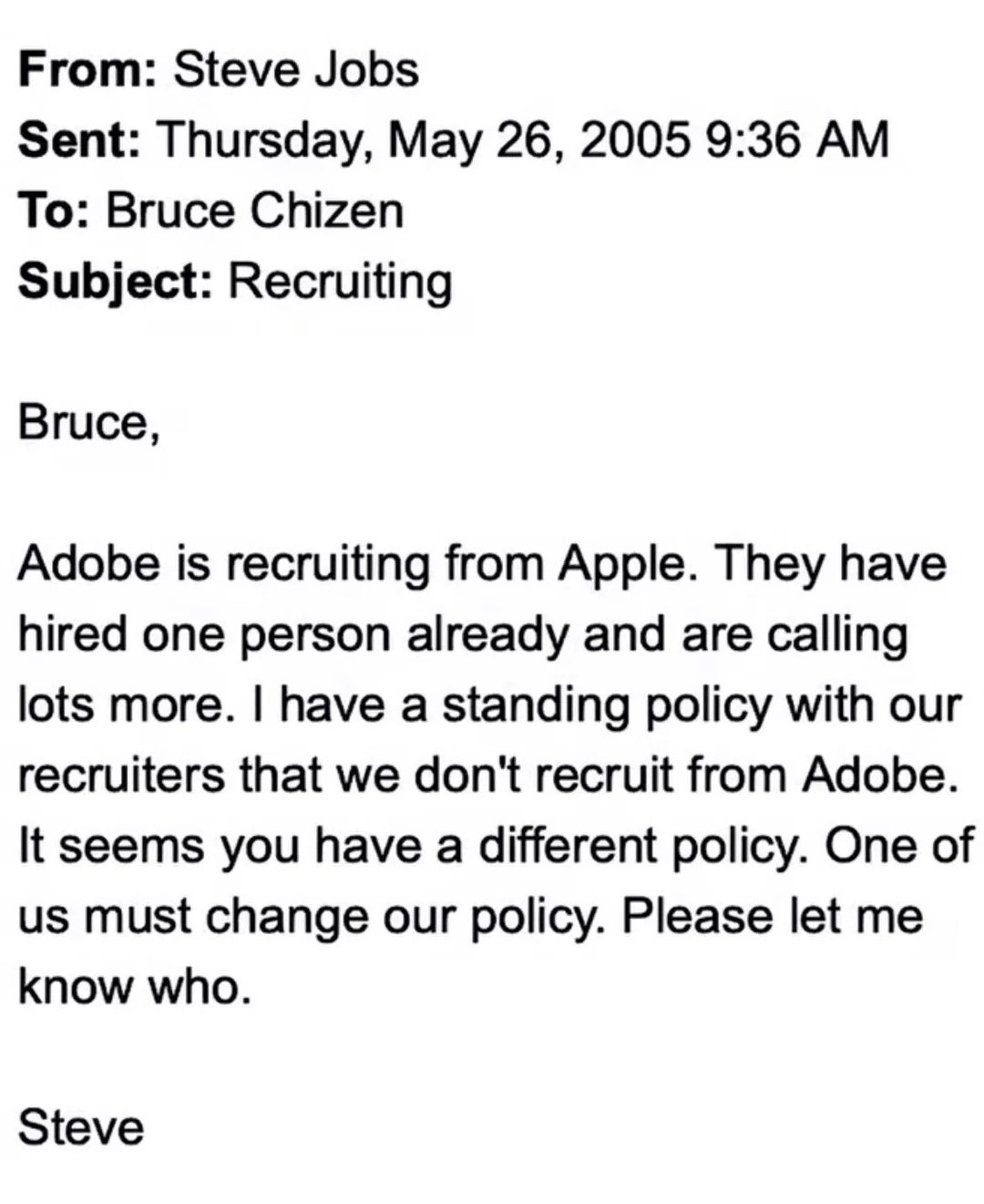

A “Gentleman’s Agreement”

Once upon a time, in the early aughts, Silicon Valley brokered an informal agreement not to hire from one another’s companies. This became the basis of multiple anti-trust lawsuits, as well as one of my favorite emails of all time:

I’ve written before about the deleterious effects that these kinds of agreement have on workers, and thankfully these agreements seem to have dissolved. Last year Sam Altman accused Mark Zuckerberg of offering OpenAI employees over 100 million dollars as an incentive to switch companies. A few months later, OpenAI bought a startup run by Jony Ive for 6.5 billion dollars, and they have been poaching Apple employees ever since.

Similarly, OpenAI and Deepmind were allegedly hemorrhaging talent to Anthropic, while Deepmind was busy getting raided by Microsoft. Assuming that Altman was honest about Meta’s humongous pay packages, these engineers are getting higher salaries than Steph Curry, Lewis Hamilton, and Patrick Mahomes. Good for them, honestly.

Everything Is Relative

This level of pay may seem exorbitant (and to be sure, most engineers are not getting this much), but the phenomena has not appeared out of nowhere. In fact, it is rooted in a transformation that has been meticulously documented for decades. Economic markets, from labor to production, have slowly turned into competitions with increasingly unequal outcomes, where victors prosper and losers live off scraps. The technical term for this is winner-takes-all; and when winner-takes-all becomes the norm, then understanding who wins—and why they win—becomes a matter of life and death.

A New Kind of “Bear” Market

A winner-takes-all market is like that story about two friends who walk through the woods and encounter a hungry bear.

Immediately, one of the men reaches down to tie his shoes, which causes the other to chide him, saying, “Are you crazy? You can’t outrun a bear!”

The friend responds stoically, “I don’t have to outrun the bear. I just have to outrun you…”

Indeed, famed economist Sherwin Rosen explained this (much more academically) in his seminal paper, The Economics of Superstars:

A winner-take-all market is one in which reward depends heavily on relative, not absolute, performance. A farmer’s pay depends mostly on the absolute amount of wheat he or she produces, and only a little on the amounts produced by other farmers. But a software developer’s pay depends largely on his or her performance ranking. In the market for personal income-tax software, for instance, the market reaches quick consensus on which among the hundreds of competing programs is the most comprehensive and user-friendly. Although the best program may be only slightly better than its nearest rival, their developers’ incomes may differ a thousand fold…

You can see this same growing inequality playing out in the eradication of the middle class, the widening disparity between average employee pay and CEO salaries, as well as the distribution of top university rankings, popular streamers, box office winners, and a plethora of other industries. Keeping to the AI theme: The Information reported that the annualized revenue of AI startups has doubled in the last seven months, yet 85% of that revenue went to just two companies—OpenAI and Anthropic. Apparently these two companies are the ones that stakeholders believe will outrun the bear.

But why is this transformation taking place? Here are the most recurring explanations, according to the literature:

Overall Acceleration of Product & Company Life Cycles

Things just move faster than they used to. Operators are wiser than ever to economies of scale, network effects, productivity tools, and management methods. Everything is online and the marginal cost of duplicating intellectual property, digital products, and software is near zero, making it disproportionally easier to scale while maintaining profits. Early wins add up quickly and even a minor head start yields rapidly compounding returns. The window of time that competitors and copycats have to enter a market is always shrinking and the distance between “startup” to “monopoly” is shorter than ever.

Replacement of Local Playing Fields with Global Competition

Modern technology has dissolved barriers between local markets, which forces all competitors into a singular, public battle ground. Whether it’s the unknown Soundcloud rapper against Drake, the mom and pop retailer against Amazon Basics, or the baby-faced intern against the veteran project manager, there’s no telling where the opposition in your respective field may come from. Spotify, Amazon, Linkedin Jobs or other, the promise—and curse—is that everyone has access to everyone. Although it seems like these technologies expand our prospects, in reality, they make them smaller. The rewards then get accrued in fewer and fewer hands.

Cognitive Biases & Seduction of Big Numbers

From an economic perspective, winner-takes-all markets consistently attract too many contestants, since the ever-increasing size of the potential prize invites larger-than-usual risks. When a certain industry is hyped beyond reason—like the AI industry is currently being hyped—it steals potential workers from otherwise suitable fields and creates a surplus of labor. To make matter worse, people are notoriously bad at discerning our own level of talent, which leads us to believe that we will most certainly be the ones who “take it all” even when we know the industry is over-saturated.

Weakened Countervailing Institutions & Outdated Policies

Since so much of the history regarding winner-takes-all markets is grounded in technology (remember rule no. 5 of understanding tech), it should come as no surprise that current U.S. policies have not caught up. Plus, it is no secret that the current administration’s agenda is overtly committed to benefiting the already-wealthy patrons and large corporations. Tax cuts and deregulatory policy have enlarged the after‑tax gains of winners, and those enlarged gains in turn finance the lobbying, campaign contributions, and agenda-setting institutions that keep those policies in place. In order to knock the momentum off of its course, alternative forms of evaluating and taxing wealth need to be considered, and a large resurgence in democratic and grassroot response needs to take place.

Conclusion & Takeaways

In summary, the rules that once dictated work, money, and meaning are changing at an accelerated rate—and people who want to avoid being bear food need to learn to think in terms of relative performance, not just absolute performance. That’s why the next dispatch will be dedicated entirely to the science behind “star performers” and the secrets of becoming one. In the meantime, consider the following advice:

Know your risk tolerance and doublecheck your competitive set. Not every space is winner-takes-all and some spaces still reward consistent, reliable contributions. Think carefully about what type of games you want to play and soberly assess how fit you are to win.

Don’t despise small beginnings. In a world where massive rewards hinge on small deltas, working on edge case advantages can sometimes yield incredible dividends. So sharpen those speaking skills, take that coding class, or start that Substack. (On second thought, scratch that last one) Do what you can to make yourself just a bit more dangerous.

Diversify, diversify, diversify. The more your income, reputation, or sense of self hinge on a single platform, employer, or algorithm, the more likely you are to be tripped and gobbled. I’m mixing metaphors now, but never put all of your eggs in one basket. I’ve written before about the merits of being a generalist. Much of that advice applies here.

And remember… what you say “no” to is just as strategic as what you say “yes” to. There is no reason that you have to be in the same bear race as everybody else.

Thanks for reading this dispatch from Mercury’s Playbook. Don’t forget to heart it down below and let me know if you found it useful.

Feathers For The Footnotes (Bonus Links)

About the Author

Bradley Andrews is a hopeful rabble-rouser on a mission to inspire the world. Stay in touch with what he’s doing outside of Mercury’s Playbook by subscribing to a weekly digest of his activity through micro.blog. This will send you writing, photos, and other curiosities that extend beyond the scope of this newsletter.

Love this perspective! It's so true how some of these massive shifts go unnoticed. The old 'gentlemans agreements' really shine a light on the ongoing talent war, especially with AI development. Makes you wander how it'll play out.

Great stuff, Brad! I suggest one unifying factor across the drivers you've listed: huge increases in the speed of information transfers that have accompanied the digital age. I think it's more of a force multiplier rather than a direct cause. Tied to this, many firms have become much better at exploiting data, whether to optimize product development, improve marketing segmentation, or identify areas of operational efficiency.

Another tidbit I'd be curious to hear your thoughts on: I'd hypothesize that the rise of the digital economy has led to a big rise in the importance of intangible capital, especially software but also IP and brand. Such intangible capital is much more inimitable than other aspects of a market-leading organization, and market concentration should follow in due time if intangible capital is both (a) more important now than it used to be and (b) super important in most industries. Thoughts?